TIFFANY GUO

Guest Blogger

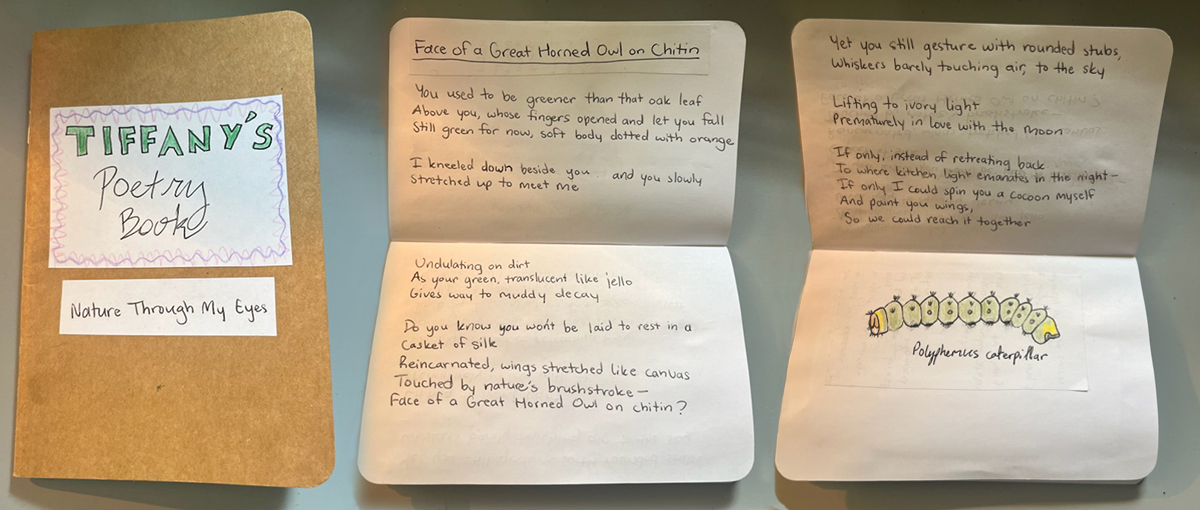

Face of a Great Horned Owl on Chitin

A poem by Tiffany Guo

You used to be greener than that oak leaf above you,

Whose fingers opened and let you fall

Still green for now, your soft body dotted with orange.

I kneeled down and you slowly stretched up to meet me

Undulating on dirt, translucent lime gives way to muddy decay.

Do you know you won’t be laid to rest in a casket of silk

Reincarnated, wings stretched like canvas

Touched by nature’s brushstroke –

Face of a Great Horned Owl on chitin? *

Yet you still gesture with rounded stubs, whiskers barely touching air,

To the sky

Lifting to ivory light, prematurely in love with the moon.

If only, instead of retreating back to the screen door –

Kitchen glow emanating in the night –

If only I could spin you a cocoon myself and paint you wings,

So we could reach the light together.

* Chitin is the fibrous, delicate material that makes up the wings of the Polyphemus moth

Over the summer, I was given an opportunity from the senior naturalist, Catie Hyatt, to complete a final project of my choice that could be used for future ideas and programs. Through this project, I wanted to leave Glacier Ridge and Homestead with a legacy that would last beyond my time there. I considered and discarded idea after idea before it came to me.

Since I started as a seasonal naturalist, I contemplated ways to illustrate human relationships to Ohio’s native wildlife through the piercing medium of language. I incorporated this in blog posts, program designs, and bulletin board ideas. For my final project, I created a booklet of poetry and illustrations to reflect my ruminations on what it really means, as people, to interact with wild animals. The poem I included, Face of a Great Horned Owl on Chitin, was inspired by the Polyphemus moths that we watched hatch, feed, cocoon, and take flight from the front porch. It happens to be one of my favorites from my collection.

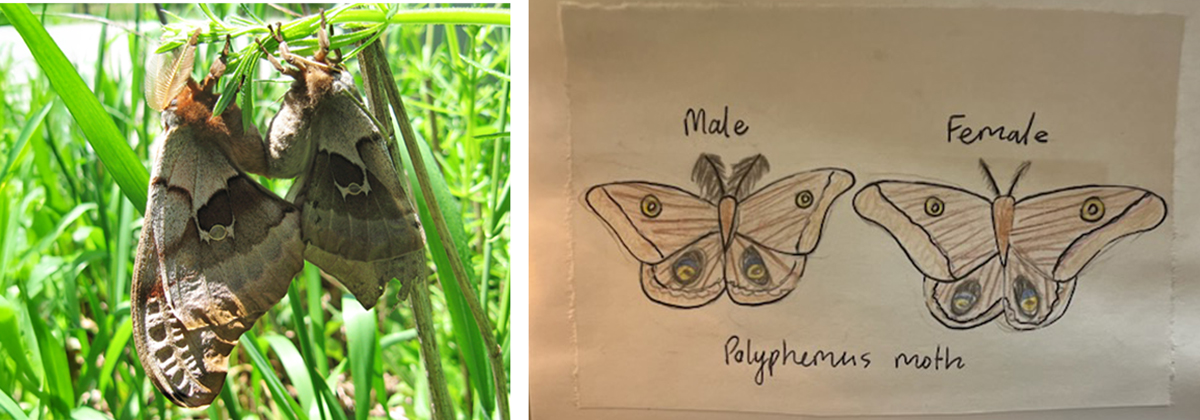

One of our naturalist projects was moth rearing. We collected the eggs of Polyphemus and monarch caterpillars in Tupperware containers, tracking their counts on a spreadsheet as they cocooned and metamorphosed. The Polyphemus caterpillars are a lime green reminiscent of squishy gummy worms, and we fed them the leaves we collected from a pin oak tree outside the office. When they emerged from their cocoons, I marvelled at their furry, bulky abdomens. Catie taught me the differences between the males and females in terms of antennae shape and body size. My favorite part of the Polyphemus moth was the magnificent blue and yellow “eyespots” on its wings, an adaptation against predators in mimicry of the face of the great horned owl.

The Polyphemus moth is a member of the large silk moth family Saturniidae. It gets its name from the Greek myth of Polyphemus, a man-eating cyclops, due to the eyespots on its wings. This moth lays small brown eggs on the leaves of a variety of trees, for the hatchlings to consume those same leaves. They need to work quickly, as their entire life cycle only lasts around three months – the egg incubates, the hatched larva (caterpillars) molt four or five times over the span of five or six weeks, and they hide themselves away in a cocoon for two weeks before emerging with wings. This cocoon stage can last longer depending on season, as they tend to emerge in the late spring and early summer. After that, their sole purpose is mating. The males use their bushy antennas to detect female pheromones, flying for miles to reach one. The Polyphemus moth is given only up to a week to reproduce before it finally dies.

I think there’s something both magnificent and tragic about that, how they eat and eat and spin and spin, only to live for a few short days. This poetry booklet not only includes those insights and observations I’m grateful to Metro Parks and Catie for, but a continually-developing attempt at mapping the intersection between wilderness and civility. In my final project, I hope to leave Glacier Ridge and Homestead Metro Parks, and the parks in general, with a glance into the prospect of meeting nature’s gaze head on, nodding to some abstract common ancestor – seeing in its eyes resemblance to our own features.

Thank you! Lovely article.