CRAIG BIEGLER

Blendon Woods & Rocky Fork Naturalist

You may be familiar with a few animals that glow in the dark; fireflies (or “lightning bugs”) and certain deep sea fish immediately come to mind. But did you know that, if you do a little extra work, there’s a whole world of glowing critters, plants and fungi just waiting to be discovered all around you?

Animals like fireflies are what we call luminescent and can produce their own visible light. Sometimes, mixing two substances together can cause a chemical reaction, which can produce new materials, heat or other effects. Luminescent organisms can create light by mixing chemicals in their bodies and combining the mixture with oxygen. A firefly has complete control over this reaction, and can “flash” its light in a certain pattern to attract a mate.

Some objects are phosphorescent, but this phenomenon is unknown to exist in living things. This is what happens in “glow-in-the-dark” toys and decorations, when the object must be “charged” by a light source before it will glow. The light slowly dims as the charge is used up.

Fluorescence occurs when something is touched by ultraviolet (UV) light, which is invisible to humans, and reflects it back to us as visible light. To us, this appears as a color boost or total change in color. We have added fluorescent materials to many objects to make their colors brighter. Highlighter markers, safety vests, blacklight posters, and tonic water are good examples of fluorescent materials. It can also happen naturally in certain minerals, as well as in many living things. Fluorescence is far more common than you would think. You just have to know how to find it.

Ultraviolet light is all around us, though we cannot see it. About 10% of the sun’s energy reaches Earth as UV light. This invisible light can be good or bad for humans. A small amount is enough for our bodies to produce Vitamin D, which is good for mental health and can help with certain skin problems. However, too much UV light can damage our eyes, our skin, and even our DNA. This is why we wear sunscreen; it reflects the extra UV away from our skin and prevents sunburn and skin cancer.

The easiest way to find fluorescent organisms is to look for them at night. Using special flashlights, you can shine UV light on whatever you want. Small UV flashlights (also known as “blacklights”) are available at most home improvement stores, and larger, more powerful lights can be found online. However, these flashlights are not toys and it is extremely important to stay safe and follow the rules. The most important rule is to keep the light away from anyone’s eyes. We all know not to look directly at the sun; treat these lights the same way.

A surprising number of living things will fluoresce under UV light, at least partially. Here is a list of some common fluorescent organisms you may find.

Millipedes are many-legged animals with a hard exoskeleton. A species discovered in 2020 has over 1,300 legs! Millipedes are easy to tell apart from their relatives, the centipedes, by their slow, calm behavior, and their two pairs of legs per body segment. The log lurker lives under leaves and logs in the forest. Under white light, this species has bright orange spots, possibly as a warning to predators; many millipedes are poisonous! When under UV light, these millipedes glow bright blue-green.

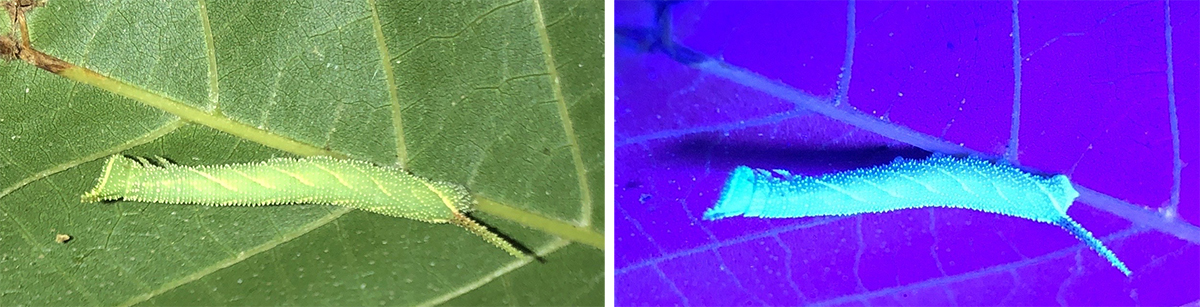

Caterpillars are often well camouflaged, since they must avoid hungry birds if they are going to turn into a moth or butterfly. Bright green caterpillars hide well among the leaves that they feed on, but UV lights can make them easier for us to spot. Look for caterpillars like the luna moth, inchworms and hornworms on native shrubs, trees or flowers.

Fungi are often fluorescent. Make sure you look at a mushroom from all angles; sometimes only the gills and spores glow. A lichen is a specialized fungus that gets energy from green algae. They can grow pretty much anywhere, even on rocks. Though they are usually a pale green color, under UV light they can be a variety of colors. Sometimes we will find two lichens right next to each other that look identical, but one will glow bright orange and the other won’t glow at all; these are two different species.

Flowers are already very colorful, but sometimes new patterns are revealed under UV light. These are thought to be a sort of “runway” for bees and other insects that might be heading into the flower for nectar and pollen. Other parts of plants can fluoresce, too: leaves, stems, bark, and even roots can glow.

Probably the most famous example of biofluorescence is the scorpion. Though we do not see scorpions in Ohio, they have some of the strongest fluorescence in the world. Scorpions are typically brown, black, or warm tones of orange, yellow or red, which helps them to camouflage on the ground. But they will all fluoresce bright aquamarine under UV light. This can be useful when traveling to scorpion territory; bring a UV flashlight and watch your step.

Even mammals can fluoresce! Since we don’t often get to see these animals up close, recent tests of museum collections have found that animals like bats, opossums and flying squirrels have fluorescent skin or fur.

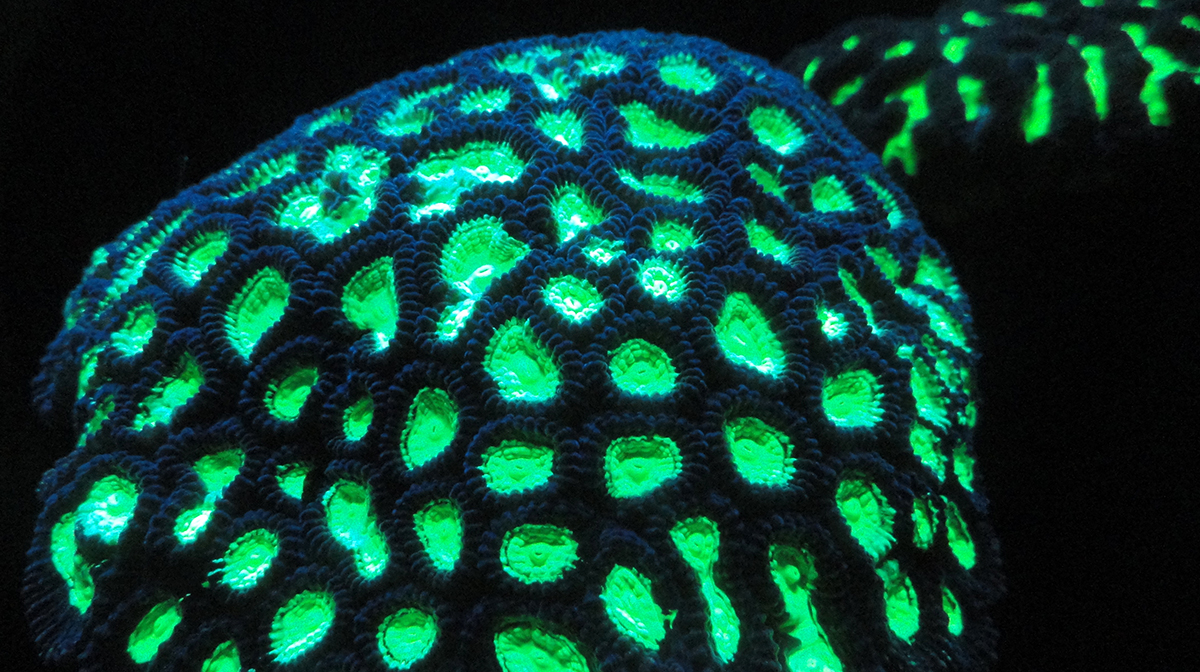

As people learn about the UV flashlight technique, more organisms have been found to fluoresce. Some slugs, spiders, crickets, daddy-longlegs, sea anemones, corals, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and even saw-whet owls can glow in this way! What else is out there to discover?

Why does this happen? Since it occurs in such a diverse range of species, we would expect it to have a purpose. Among the animals, it seems to occur most in nocturnal creatures or ones that spend a lot of time hiding in the dark. The scorpion provides the clearest explanation for its fluorescence. Despite their venomous stinger and formidable claws, scorpions are often prey for larger animals. They do not want to be caught out in the open during the day or they may be eaten by a bird or a lizard. They also have very poor eyesight, so they may not see a predator until it’s too late. However, their eyes are particularly sensitive to the color green. The idea is that a hiding scorpion would notice if a part of its body was exposed to sunlight because the UV light would cause it to fluoresce, compelling the scorpion to find better cover. From my own experience, I have noticed that scorpions do not sit still when exposed to UV light, so there may be something to this. Another example of functionality is that flowers sometimes have fluorescent patterns that are only visible to the insects that pollinate them. But does this explain the wide variety of living things that possess this trait? What about the lichens, who do not need pollination and are always out in the open? We may never know all the specific reasons that living things fluoresce, and it’s possible that it doesn’t always serve a purpose.

If nothing else, it’s fun! This is a great way to explore nature in a new way and to make discoveries in your own community. Get out there and see what you can find!