VIRGINIA GORDON

Communications Coordinator

Don’t you just love it when a plan comes together? Metro Parks was very much part of the A-Team, the John ‘Hannibal’ Smith of the moment, when a plan came together in 2004 for a Metro Park, a major inner-city park, on the Whittier Peninsula in downtown Columbus.

Wait? A what? A Metro Park on the Whittier Peninsula? That old industrial dump! Haha! You gotta be crazy!

Listen carefully, and you can still hear the laughter on the river breeze.

A VISIONARY FUTURE

The doubters had every right to laugh. Indeed, many a rational mind would have seen it as a crazy idea, at first sight, to want to transform an industrial brownfield site so recently blighted by major pollution spills into a 120-acre Metro Park. But the winds were already turning. In 1998, the Columbus Riverfront Vision Plan had been published, inspiring political commitment toward long-term development of the Scioto River corridor in downtown Columbus.

Metro Parks had a vision too, for an inner-city park. At the time, Columbus and Franklin County Metro Parks had 11 parks, but none were within the urban core of Columbus itself. That was something Metro Parks wanted to change. Among the park district’s many commitments when seeking voter approval for a Metro Parks Levy in 1999, Metro Parks promised to work with various local municipalities to finalize the Greenways Initiative, creating trails along the region’s major river corridors. It also promised to develop and open a new park in downtown Columbus. Scioto Audubon Metro Park was the eventual result.

Metro Parks’ partners in their crazy but transformative idea were Audubon Ohio, which was also keen to establish an urban presence, and the City of Columbus, which had owned land on the peninsula since the 1950s.

CRAZY? NOT HALF, IT AIN’T!

The Whittier Peninsula is a bulge that shapes a womb-like bump in the contour of the Scioto River. That it might eventually birth such a resplendent child as the Scioto Audubon Metro Park was as far removed from people’s thinking as the notion that Santa Claus was real and played linebacker for the Cleveland Browns when he wasn’t out and about with his reindeers on Christmas duty. Never… listen up, people… never gonna happen!

But where there’s a will, there’s a way. Even today, it is hard to imagine how such a glorious child came from so hideous and unlikely a parent. As the 20th Century neared its end, the Whittier Peninsula was mostly derelict and blighted by the pollution of almost a century and a half of largely unregulated industrial activity.

AN UGLY BUT INDUSTRIOUS PARENT

Yes, the Whittier Peninsula was in a sorry state as a new millennium dawned, but in its own terms, it had played a long and important role in the development of Columbus as a city. In the city’s early days, the peninsula brought prosperity via its transportation channels. As early as 1827, construction had begun on the Columbus Feeder Canal, running north to south near the eastern boundary of the peninsula. It connected Columbus to the Ohio Erie Canal, joining it at Lockbourne. It was a vital cog that helped the capital city to grow economically and in influence. Within a couple of decades, the coming of the railroads expanded the city’s prosperity and influence even more.

THE RAILROADS

The Hocking Valley Railroad Company and the Toledo & Ohio Central Railway Company operated from the Whittier Peninsula, transporting coal and other goods. They built machine shops, repair shops, a railway roundhouse, and massive coal bins, freight and warehouse depot buildings. The entire peninsula hummed with industry. In time, these railroad companies merged, and joined with a third company to become the Columbus, Hocking Valley and Toledo Railway Company. In turn, by about 1930, the holdings of the company were acquired by the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad Company (CSX), which runs the remaining railroad lines today. The remaining railroad tracks lie outside the eastern boundary of today’s Scioto Audubon Metro Park, in the area where the feeder canal used to be. The canal had ceased its useful life in 1904.

INDUSTRY AND POLLUTION

The western portion of the Whittier Peninsula had long been utilized for industry. Over time, the peninsula buzzed with several saw mills, hosted a steel mill, sand and gravel companies, cement and asphalt manufacturers, and other industrial companies. Lazarus & Company bought land in the central section of the peninsula soon after the end of the Second World War and built a massive warehouse, used for both furniture manufacturing and as a distribution center.

Parts of the peninsula that had been used for railroad maintenance and as a switching yard were sold off from the 1930s onward, and eventually came into the ownership of the Maier family, which built a second huge warehouse on site, north of the Lazarus warehouse. In 1980, parts of the Maier warehouse were used by Harper Industries, which worked in metal fabrication and electroplating of automotive parts. There were a number of sad and sorry mishaps on site. In 1985, Harper Industries were responsible for a number of major industrial spills of damaging chemicals, including paints, cutting oils and solvents. The company filed for bankruptcy and abandoned their warehouse sections, which were left in a state of disrepair and contamination. It remained vacant and contaminated for years, until the Maier Foundation issued a declaration in the year 2000 that all of its related activities on the peninsula were formally at an end.

THE CITY PRESENCE ON THE PENINSULA

The City of Columbus had operated a landfill on the peninsula in the 1930s. In the late 1950s, the city’s Refuse Department filled in some ponds on the peninsula and built an incinerator unit there. It would eventually fold and become part of the city police’s vehicle impound lot, which began operating there in the 1960s. In 1985, the size of the impound lot was doubled, and it became the holding site for impounded or abandoned vehicles, many of which were left to rot there. At any one time, there were more than 5,000 vehicles on the impound lot.

The city’s Parks and Recreation Department even had a small park on the peninsula, known as Lower Scioto Park, which opened in 1962. The park wouldn’t last long. Most of it was also subsumed into the police impound lot. Other recreational efforts on the peninsula included a boat ramp, or marina, added in 1968, and a bike trail along the river’s edge, which was constructed in 1977. This trail would later be repurposed as a Greenway Trail. The boat ramp was renovated and improved as part of a Whittier Boat Ramp project, bid out by Metro Parks in May 2006. But here we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

After the Lazarus Warehouse closed, and other industries on the peninsula began to fold, the City of Columbus took ownership of more land on the peninsula, aided by several grant programs, but didn’t have the resources to develop it.

TURN OF THE CENTURY

Galvanized by the Columbus Riverfront Vision Plan, Metro Parks embarked on its first discussions with the City of Columbus and with Audubon Ohio in 2001. By 2004, it led to a formal agreement between the three partners. Crazy as it seemed, there would indeed be a Metro Park coming to the blighted Whittier Peninsula in downtown Columbus. One enthusiast declared at a public meeting that they would love to see Highbanks on the Whittier Peninsula. Well, there was no way of transplanting a 100-foot-high shale bluff to downtown Columbus, but little else was ruled out!

The plans of the real… er, that is, the fictional… Hannibal Smith used to come together and then come to fruition all within the course of one hour (or 44 minutes without commercials)! The plan that came together for a Metro Park on the Whittier Peninsula would take years to come to fruition. But everyone involved knew the wait would be worth it.

A DAUNTING TASK

When the three partners began their discussions, they knew they would face a major challenge from soil contamination. An Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report, from 1998, revealed high levels of contamination on the peninsula. Numerous abandoned industrial buildings had leaked contaminants from underground storage tanks. It anticipated finding high levels of heavy metals and semi-volatile organic compounds in the soil, which would later prove accurate. The old Lazarus and Maier warehouses were also confirmed to harbor high levels of asbestos.

Undaunted, the partners made an agreement. The City of Columbus, which had taken possession of even more land on the peninsula after the Lazarus Warehouse closure, agreed to lease roughly 74 acres to Metro Parks for 25 years, at a cost of $1. This agreement was later extended, to three separate 25 year lease periods, each period at a cost of $1. In turn, Metro Parks agreed to sub-lease about 5 acres of land to Ohio Audubon, to be the site of a future urban nature center.

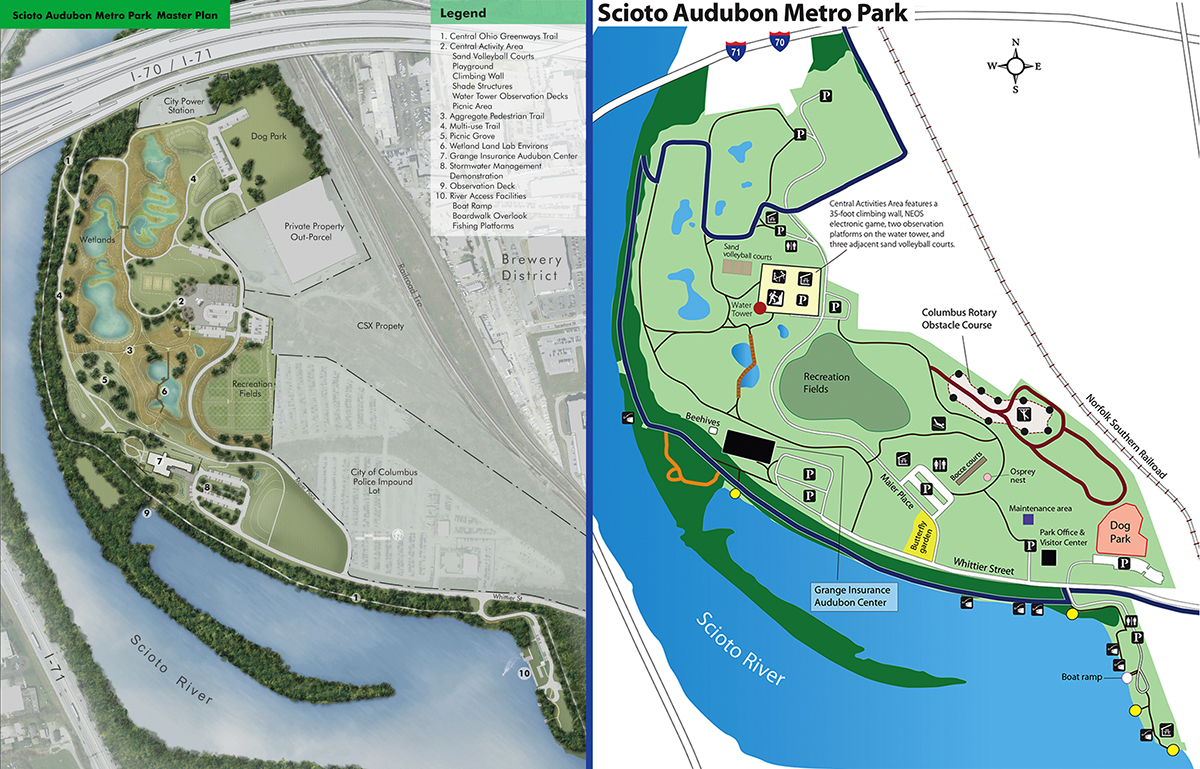

A Metro Parks project team, led by Deputy Director Larry Peck, coordinated what was then known as the Whittier Peninsula Metro Park group. Each of the partners, Metro Parks, Audubon Ohio, and the City of Columbus, formulated their individual goals for development of the park and its facilities. Slowly, as a vision emerged, a master plan came together and was published in 2005. Discussions turned frequently to the grave issue of pollution on the peninsula and how to tackle it.

BROWNFIELD REMEDIATION

Brownfields were defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as unused or disused sites that bore signs of contamination by hazardous substances or pollutants or had the potential for such contaminants to be found there. The Whittier Peninsula qualified strongly as a brownfield. In 2002, the so-called Brownfields Law (formally known as the Small Business Liability Relief and Brownfields Revitalization Act) had been passed by the federal government. The law was established to provide grants to local governments to assess, clean up and revitalize brownfields.

Using its status as a local political subdivision of the State of Ohio, Metro Parks made the Clean Ohio Assistance Fund application in August 2004. For the first phase of development, Metro Parks’ application for remediation funding promised that cleanup and demolition of the Lazarus Warehouse and adjacent property on the Whittier Peninsula would serve as the catalyst for the revitalization of the entire peninsula. The application pointed to the public support for the project, and of letters of support from Audubon Ohio and the Brewery District Neighborhood Association. The first phase was intended to provide momentum to implement the vision outlined in the the 1998 Riverfront Vision Plan. A grant of $742,000 was awarded

THE CLEANUP BEGINS

In order to coordinate the remediation of the site, Metro Parks and its partners hired Columbus-based companies, including Kinzelman Kline Gossman and Burgess & Niple. They were tasked with providing the necessary environmental engineering and remediation services to qualify the site for EPA approval as safe for development. This included the safe removal of asbestos from the Lazarus and Maier warehouses before they could be demolished. The part of the Maier warehouse that was remediated and demolished was on a 10-acre plot of land which Metro Parks needed to purchase from the Maier Foundation. That purchase brought the initial acreage of the future park up to 84 acres. The warehouses were demolished in 2008.

By the middle of 2006, more than 9,000 cubic yards of polluted soil had been removed from 11 different areas of the future park, partially replaced by more than 2 feet of clean fill. Wetlands were created in some of these excavated sites, using geosynthetic liners, and landscaped with native wetland plants. The wetlands were designed to aid stormwater management on site and become self-sustaining natural habitats that would naturally constrain or remove more low-level pollution.

SUCCESSFUL CLEANUPS

Metro Parks entered the remediation project into the Ohio EPA’s Voluntary Action Program, which led to approval to develop the property as a park via four No Further Action Letters and Covenants Not to Sue from the Ohio EPA. These remediated areas were for a 26-acre parcel of land on which the Audubon nature center would be built, an 18-acre parcel northeast of the Lazarus warehouse, the 13-acre site on which the Lazarus warehouse had stood, and later on, the 40-acre former police impound lot.

THE PARK GETS A NAME

At the Metro Parks Board Meeting in July 2007, the three-member board of park commissioners formally adopted a name for the new park. The park would be named Scioto Audubon Metro Park, to celebrate Metro Parks’s partnership with Audubon Ohio, and to honor its location on the Scioto River. Some parts of the park were available to users in 2007, including the renovated boat ramp and a fishing dock on the river, which boasted a new parking lot with native landscaping. By the end of 2008, Metro Parks had spent about $10 million on developing the new park, about half of which had gone towards cleanup and remediation.

Metro Parks’ Deputy Director Larry Peck said at the time, “For Metro Parks this was an investment. We used funds from the Clean Ohio Fund, which at heart is an economic redevelopment program, and our goal is to make recreation spur jobs and to attract skilled workers by improving quality of life. We think a lot about how this fits into the economy of the city.”

POLLUTION SCARES OFF THE DEVELOPERS

The City of Columbus planned to move the old police impound lot off the Whittier Peninsula and use the 40 acre plot for housing. As such, it was part of the initial concept for development of the Whittier Peninsula, which envisaged an 80-acre park and about 55 acres of residential/office/commercial development.

That initial concept envisioned up to 2,000 units of affordable housing. But developers were wary of the challenges of building houses on a brownfield site. There would also be a requirement to build a bridge, which developers found unappealing. Plus, many developers were engaged with projects out of state, tackling issues arising from the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. By late 2008 the housing development plan was abandoned by the city, which asked Metro Parks if they would expand the Scioto Audubon Metro Park by these 40 acres. At the same time, the city asked Metro Parks if it could take over the maintenance and security patrol of the Central Ohio Greenway Trails, including the Scioto Greenway Trail, which ran through the park. As the city also indicated it would be unable to pay toward operating expenses at the expanded park, Metro Parks had to make the expansion plan a part of its next 10-year Levy proposal, which was due to be voted on in 2009. With the passage of the 2009 Metro Parks Levy, Metro Parks was able to commit to the expansion plan. But nothing could be done until the police impound lot was moved off the peninsula. In the meantime, the original 80 acres allocated for the park was scheduled for an official opening in August 2009.

TALK TO THE BIRDS

The birds knew it! And birders knew it! The Whittier Peninsula wasn’t entirely without hope! That stretch of the Scioto River that curved around the peninsula’s western edge had become a major fly-by for migrating birds. The attraction for birds included a narrow forest strip along the peninsula side bank of the river, and the fact that the water channel itself widened considerably over this stretch of the river.

The wider river channel here traces its expansion back to one of Columbus’s worst floods, which happened in March 1913. The Scioto River rose quickly by about 10 feet and broke all the existing levees. The resulting flood destroyed hundreds of buildings and 90 people drowned. A new levee was built on the western side of the river, occupying the entire stretch of the Whittier Peninsula’s eastern shore. By the 1920s, a large area of land on the southern end of the peninsula was lost permanently to the river expansion, where the river was at its widest. In the 1940s additional levees and dam and bridge enhancements were built, and over time a strip of vegetation began to emerge in the widened river.

Today, that strip of emergent vegetation is nicely forested and forms an inlet around the river bend at the southern end of the peninsula. This resemblance to the Baja Peninsula in California even had people suggesting Baja Metro Park as the name for the then unnamed new park on the Whittier Peninsula. It added to the attraction for migrating species as a stopping place, and Audubon members and birders in general came to appreciate the western edge of the peninsula as a must-go place to see birds. The levee itself was landscaped and a bike trail was built on it.

THE AUDUBON CENTER

Audubon Ohio set to work on both the design and funding for an 18,000-square-foot nature center inside the new Metro Park on the Whittier Peninsula. It was always intended that the building would serve as a model for sustainable design and it was planned to have a plant-filled green roof, and be heated and cooled by geothermal energy sources.

The center’s primary purpose was to provide educational services for public schools, especially those in the inner city, and to provide a resource and meeting place that would help in the vital task of increasing environmental awareness for visitors and the wider population of the city.

In 2007, the Columbus-based Grange Insurance paid $4 million to buy the naming rights for the the new center, which would become the Grange Insurance Audubon Center. American Electric Power provided a gift of $1.5 million for the project, as did Franklin County, while Limited Brands contributed $1 million to the $14.5 million price tag for the center. Other major donors included the Solid Waste Authority of Central Ohio, Columbus Foundation, Huntington Bank, Crane Group and the Family and All Life Foundation.

Groundbreaking for the center began in July 2008, soon after the Ohio EPA greenlit the project by granting its first approval of the Metro Parks remediation project. It was ready for its grand opening in August 2009. Glass, wood and metal were the major building materials for the center, which features full-height windows to capture views of Downtown Columbus on one side and the park’s wetlands and trees along the river on the other side. The windows include bird patterns embedded in the glass, which break up the reflective surface. As well as being aesthetically pleasing, the embedded bird patterns allow birds in flight to recognize that these massive windows aren’t open-air fly throughs and so have considerably reduced the number of potential collisions.

The center has proven to be an incredible success with schools and visitors. It includes three classrooms, a 200-seat multipurpose room and library, and is often used for art exhibits on nature themes.

THE CLIMBING WALL AND OTHER ATTRACTIONS

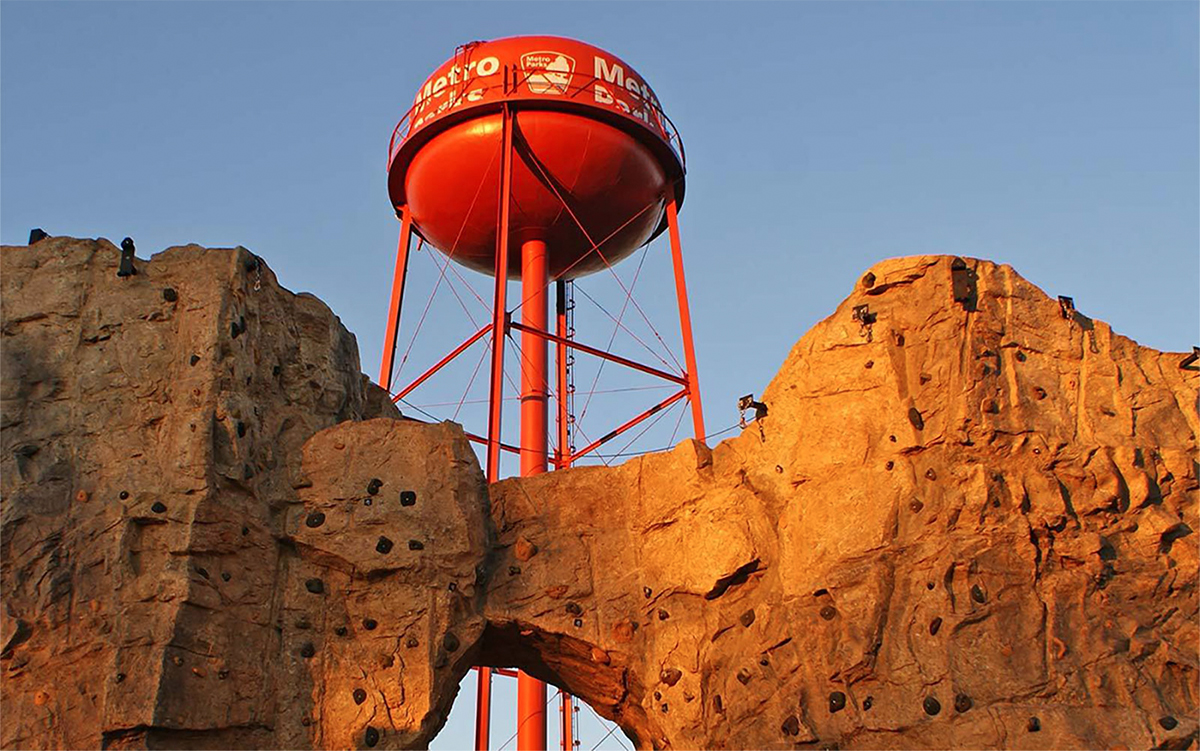

One of the core aims of the partnership was to help attract people to live and work Downtown. In support of that aim, Metro Parks set out to appeal to young professionals and commissioned the construction of a 35-foot-high fiberglass and concrete climbing wall. The wall was constructed from molds taken from real rock faces and boulders. It includes three towers and two arches and stretches to more than 7,000 square feet, making it the largest outdoor climbing wall in the mid-West, and bigger than many full-size indoor climbing gyms. Two 8-foot boulders were also constructed for novice climbers. At a cost of $600,000, the climbing wall allows up to 20 climbers at a time, and features four auto-belays. Climbers need to bring their own ropes and equipment.

The wall was built on a rubber flooring, laid down on the area where the Lazarus warehouse had once stood. A derelict water tower was renovated and two observation decks were added to the tower, to provide high lookout points across the adjacent wetlands.

Also, in what became called the Central Activities Area, Metro Parks built a bird-wing like shade shelter and seating, and installed an interactive electronic game, free to use, called Neos. Three sand volleyball courts were also built nearby.

THE ADDITIONAL 40 ACRES

In December 2010, the Metro Parks Board formally approved an agreement with the City of Columbus to acquire the city’s police impound lot. The city moved the impound lot to a location south of State Route 104 in October 2010, but not all of the vehicles on the old Whittier Peninsula lot were moved until summer 2011. Ohio’s state controlling board approved a $1.5 million Clean Ohio Fund grant to Metro Parks to clean up the found contaminants on the old impound lot. While these remediation efforts were being performed, Metro Parks consulted numerous community groups about the kind of facilities they would like to see in the additional 40-acre section of the park.

The Columbus Rotaract Club, a registered student organization at OSU, which aims to provide young men and women with opportunities to tackle social and physical needs in their communities, created a Facebook page to solicit more ideas. Wish lists included items such as a zip line, an outdoor theater, and a sledding hill. But the top request was for an obstacle course. The Rotaract Club, sponsored by Columbus Rotary, submitted their idea to Metro Parks.

THE COLUMBUS ROTARY OBSTACLE COURSE

The obstacle course was taken onboard as a project by Columbus Rotary in 2012, to celebrate the club’s centenary. The club provided more than $100,000 in donations and in-kind services in order to design the course and build it in the 40-acre park extension. It opened with a grand opening ceremony on October 26, 2013, with a challenge team run between competing gropus from Metro Parks, Columbus Rotary, The Ohio State University ROTC, and other groups of young professionals. The free course includes a tire run and flip, a tunnel crawl, a cargo climb, a balance beam, a belly crawl, monkey bars, an over/under, a climbing wall, and a log run, as well as a half-mile trail around the obstacle stations.

Columbus Rotary President Steve Heiser said, “Fellow Rotarians were enthusiastic and committed wholeheartedly to helping Metro Parks enhance the outdoor amenities at Scioto Audubon that ultimately contribute to the health and well-being of the Central Ohio community.”

MORE FACILITIES FOR THE EXPANDED PARK AREA

In addition to the obstacle course, Metro Parks extended the existing recreation fields, built three picnic shelters, with tables and grills, created a bocce court, and moved the park’s office and maintenance building here.

THE DOG PARK

In 2010, Metro Parks built a 2.5-acre dog park in the northeast sector of the park, where the demolished section of the Maier Warehouse had once stood. There were separate sections for large and small dogs. It became one of the park’s most popular features and was the site for Metro Parks’ first ever Yappy Hour. It was a great facility for pets and their owners, but eventually it was necessary to move the dog park to the old impound lot site.

Plans had been mooted by the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) in late 2008 for improving the I-70/I-71 corridor downtown, and gave notice that the plans might impact the northern area of the then still unopened Scioto Audubon Metro Park. But these plans weren’t expected to impact Scioto Audubon Metro Park until around the year 2016. In the end, implementation of ODOT’s plans were considerably delayed, and work did not begin until February 2022. However, ODOT gave notice to Metro Parks that they would need to use the dog park to stockpile construction materials when work began on that particular phase of their multi-year interstate ramp-up projects.

Metro Parks also agreed to sell a little more than half-an-acre of park land to ODOT for the highway improvements, and ODOT agreed to pay for the relocation of the dog park to the old impound lot site. Almost half of the new 1.5-acre dog park has an artificial turf surface, which eliminates the problem of muddy ground after bad weather. Like the old dog park, it has separate, fenced-off areas for both large and small dogs. There are a number of play structures and obstacles in the artificial turf areas, including a tunnel tube, balance beam and jump obstacles. It has met with canine approval.

THE REVERSAL

At the start of this article, I posed the somewhat facetious argument that people would find it hard to imagine how such a glorious child as the Scioto Audubon Metro Park came from so hideous and unlikely a parent as a blighted and abandoned industrial site. But for many people today, the reverse applies, and they would find it difficult to acknowledge that this beautiful natural landscape was once a derelict industrial wasteland. Come visit Scioto Audubon Metro Park and see the beauty for yourself.

Great job. What great use of this land and keeping it from being more housing. You’ve done a great job of increasing the number of parks and facilities in central ohio, but I think we have enough now. Hopefully you’ve considered the cost of upkeep. As seen with the “rails to trails” intinatives, they are often built but soon unkept and forgotten. The biggest problem is roots protruding and obstructing the paths. Please consider this. Thanks again.

I really enjoyed reading about the history of this site and the emergence of the Park, which I often visit.

Very informative and well written! I remember the peninsula when it was home to a Lazarus warehouse/store, as well as a building for the adult sports office for Columbus Recreation and Parks and the city impound lot which held hundreds of vehicles leaking gas, oil and other fluids into the ground. Thanks to taxpayer dollars and Metro Parks it now is truly a gem for Columbus. Central Ohio needs Metro Parks to continue to move in this direction. All of us are stewards of this land and we all contribute to minimize the upkeep mostly through our tax dollars and a few sign-on as a park volunteer. We are all responsible. Friends of Metro Parks and volunteers work with Metro Parks to see that all 20 parks which include the attached “rails to trails” are not left “unkept and forgotten” unfortunately “protruding roots” are a part of the ecosystem, and the trees allow us to recreate in their habitat. The peninsula has created a new habitat for countless birds that visit our capital city including the bald eagles that nest across Greenlawn Ave at Berliner Park on top the light poles. In the spring if you’re at Berliner near diamond 4 or 7 or 8 you can hear the fledglings or chicks in their nest at the top of the light pole screeching for more food. I’m certain they are nesting somewhere in Scioto Audobon as well along with the Osprey and several hundred other feathered friends.