VIRGINIA GORDON

Communications Coordinator

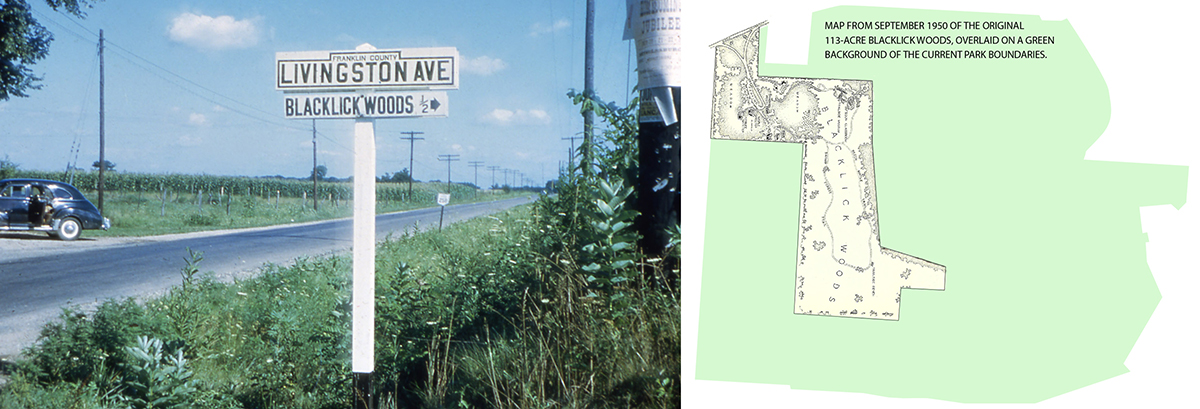

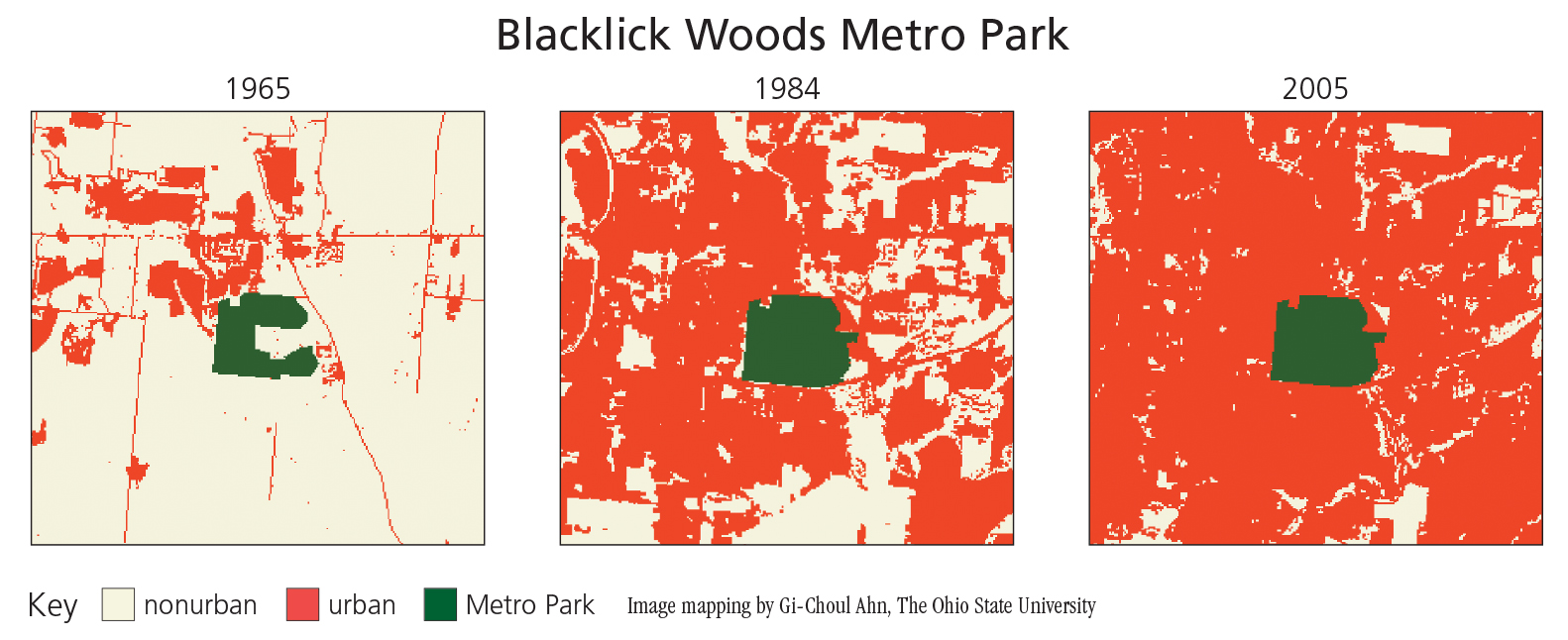

Seventy-five years ago, this October, the first park in the Columbus and Franklin County Metropolitan Park District opened its gate to the public for the first time. Today a 643-acre park with a state nature preserve and a highly regarded public golf course, Blacklick Woods Metropolitan Park opened in 1948 as a 113-acre stretch of woods and open meadows.

THE POLITICS OF PARKS

The path leading to the opening of Blacklick Woods goes all the way back to the Ohio Legislature’s enactment of the Ohio Park District Law in 1917. The law was formulated in response to lobbying by conservationists about the need to preserve natural scenery, streams and woodlands near Ohio’s big cities, so they could be enjoyed by future generations. Communities were empowered by the law to establish park districts with limited taxing powers and authority to acquire land for natural area parks. These lands were to be used for conversion into forest reserves and for conservation of the natural resources of the state.

Many years would pass before Columbus took advantage of the opportunities presented by the 1917 Ohio Parks Districts Law. Cleveland joined the game at start of play, and established the Cleveland Metropolitan Park District before the year was out. Akron established its metropolitan park district in 1923, Toledo in 1929, and Cincinnati created the Hamilton County Metropolitan Park District in 1930.

COLUMBUS AND FRANKLIN COUNTY JOINS THE GAME

In 1945, a Metro Parks Study Committee, made up of central Ohio naturalists from the Wheaton Club, produced a compelling report, which endorsed the creation of a local Metropolitan Park system,. The report also included a detailed inventory of the natural resources of Franklin County and the need to preserve them. Presented at a public hearing on August 14, 1945, the report heralded the creation in law, that very day, of the Columbus and Franklin County Metropolitan Park District. The president of the committee, Walter A. Tucker, was invited to become the temporary secretary of the new organization, a post that would be made permanent two years later.

Metro Parks hired its first park planner in 1946 (although the post-holder was initially and officially employed by the Franklin County Planning Commission, as Metro Parks didn’t have funds until the following year). The director-secretary and park planner inspected sites that might work as future parks. On January 1, 1947, the new Metropolitan Park District acquired its first budget. Land acquisition was the priority, and the first acquisitions, in March 1948, were of three tracts of land identified in that original inventory. As written in the 1945 document, it describes the first phase of the future Blacklick Woods as follows:

Livingston Avenue – Blacklick Woods

A large unspoiled woodland with many large, original trees still standing, situated south of Livingston Avenue and west of Blacklick Creek in Violet Township, Fairfield County. Few woodlands in the vicinity of Columbus possess as great an abundance of wildflowers and wildlife as this one woodland. About one-half of the forest consists of the beech-maple type, the remaining being swamp forest where the soil is apt to be wet during the driest months of the year. It is the refuge of many rare birds and wildflowers and is most worthy of preservation for future generations.

BLACKLICK WOODS METRO PARK OPENS

The park district hurried to make its new park ready for an official opening and dedication ceremony on October 24, 1948. Reynoldsburg, with a population of just above 700 people back in 1948 (at the 2014 census the population had increased by more than fifty-fold), was far from the built-up area it has become today, and some people worried that Blacklick Woods was “too far out in the country” to attract many visitors. The worry was unfounded. It was apparent, very quickly, that demand vastly outstripped the available facilities. But solutions would have to wait.

At the opening of Blacklick Woods, visitors had well-graded roads into the park and parking for 80 cars, with picnic facilities that could easily accommodate 400 people. There were 50 picnic tables, stone fireplaces with metal grill tops, and a new 136-foot well for pure drinking water. Development of the park continued, and by 1950 the park had three picnic shelters, a trailside museum and outdoor classroom, a trading post, plus nature trails that took people through the beech-maple and swamp forests. The trading post sold firewood and charcoal for picnic grills.

The trailside museum served as a starting point for nature programs and bird walks, and was sometimes used in conjunction with the outdoor classroom, a small amphitheater seating up to 125 people on rustic benches. Initially, Metro Parks employed graduate students to lead nature walks and help out with educational programming. Schools would visit regularly, and kids seemed to enjoy seeing animals in the small trailside zoo houses. Some of these resident animals became celebrities. Sam the Red Fox appeared on television several times during the early 1950s, and Jerry the Coyote lived at the zoo throughout the 1960s.

The rationale behind the trailside zoo argued that it was easy to see the park’s wildflowers and trees, and to see and hear the birds, but most of the park’s mammals, being largely nocturnal, would only move around after dark, when the park had closed. After 20 years of operating the trailside zoo, the displays held up to 75 animals, from about 25 different species. Each spring, new animals would arrive, either through births amongst the resident animals, or injured or orphaned animals found in the park. Although the animals were fed a healthy diet and were always well-cared for, and despite the trailside zoo being a popular attraction, the burgeoning weight of objection to caging animals in a natural area park became too big to ignore. The trailside zoo was phased out during the mid 1970s, whilst the concept of an ‘aura room,’ as described by one park naturalist of the time, envisaged animals being lured into natural areas, to be seen by ‘unseen’ people. The initial idea of creating a hidden observation room, with people hidden behind one-way glass, proved unsupportable on the scale needed. But the nature center planned for the late 1970s included viewing windows, looking out over a newly dug pond with an adjacent natural swamp, which would become mud-flats in summer and attract numerous shore birds. The nature center viewing windows continues to be a wonderful way to watch wildlife at the park. Deer, fox, raccoons, squirrels, waterfowl and many species of birds are regularly “on display.”

DAY CAMPS

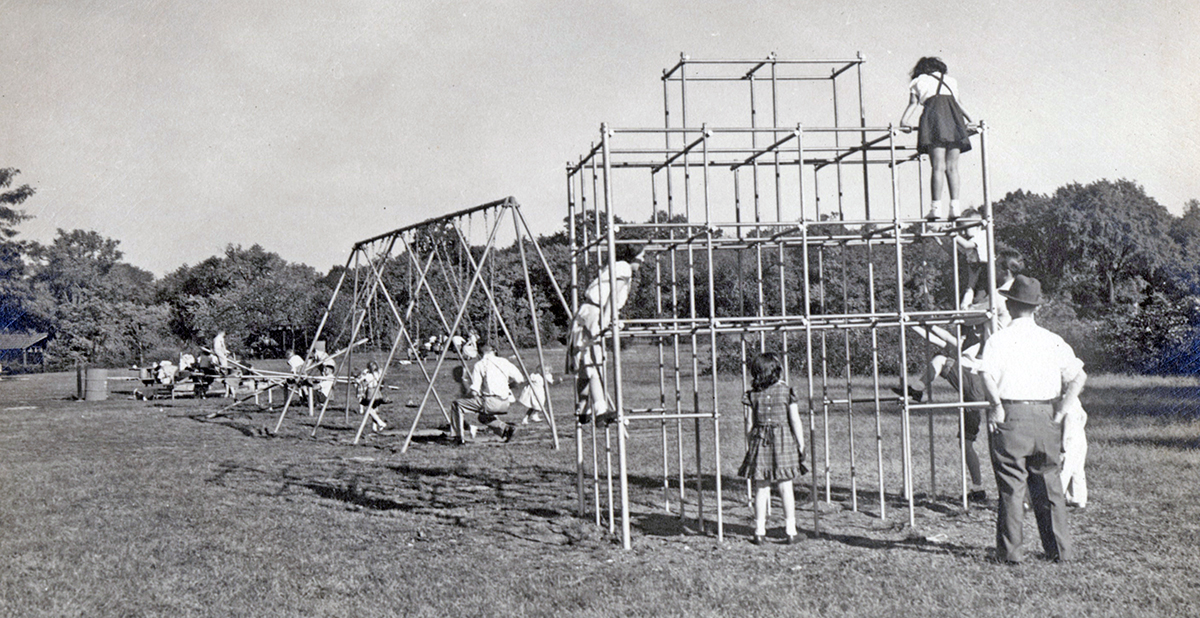

Blacklick Woods was in demand by groups wishing to organize day camps at the park. Camp Fire Girls were first on board with a day camp at Blacklick Woods in 1949. They set up a tent as their base and used the tent again in 1950 and 1951, and were then allowed to build their own timber-frame shelter on site for future years. The Columbus Jewish Center also utilized Blacklick Woods for day camps in the early 1950s, and were later joined by Ohio Girl Scouts and the YMCA.

THE LODGE

Picnic facilities were used heavily during the summer months, and although Metro Parks added two new shelters in the early 1950s, demand continued to exceed supply. Larger groups also sought to have larger shelters or meeting facilities available within the parks. It was hoped that the opening of Blendon Woods in 1951 might spread out the demand somewhat, but instead it actually fuelled the public appetite for more shelters in the parks.

In May 1951, the Bexley Garden Club of Columbus voted to donate a thousand dollars to Metro Parks as the start of a public fund to build a large shelter at Blacklick Woods. Other organizations began to make donations to the fund too. Camp Fire Girls gave $500 from their candy sales, and other contributors included Columbus Audubon, The Columbus Foundation, Kroger Grocery and Bakery, The Wheaton Club, and Kiwanis Clubs. The failure of the 1951 Parks Levy limited what Metro Parks could do in terms of park development, but the need here was obvious and work eventually proceeded.

Initial plans for a large three-quarter covered shelter were modified in favor of a fully-winterized enclosed lodge. By August 1955, the new Beech-Maple Lodge was ready for opening. The rustic style oak-shelter house, with its own parking lot for 30 cars, separate kitchen and meeting room and large stone fireplace, could hold up to a hundred people for dinners and meetings. The lodge was available by reservation only, with nominal fees to cover repairs and upkeep of the property.

A NEED FOR GROWTH

Despite the success of the Beech-Maple Lodge, demand for picnic and meeting facilities continued to grow, but Blacklick Woods had no more space for further facilities. The old-growth woodlands occupied 73 acres of the site, so only the remaining 40 acres were available for development, and they were now heavily over used. In 1951, Metro Parks ceased advertising Blacklick Woods through the summer, as they couldn’t cope with the demand by picnickers. Even the addition of two more family-size shelters that summer, making five shelters in all, did little to help. Cars had to be parked on the grass all that summer, prompting the grading of a 300-foot addition to the parking lot. A second park, Blendon Woods, opened in 1951, but people still wanted to come out to Blacklick Woods and the demand never slackened.

From its opening at the end of October 1948 through to the year end for 1960, more than one and a quarter million people had visited the 120-acre park (a 6.5-acre parcel had been added to the original 113 acres in May 1958). Overcrowding had led to a need for overflow parking, damage of natural areas, and public irascibility at the lack of immediately available picnic facilities.

BLACKLICK WOODS EXPANSION

The passing of the first successful Metro Parks Levy by Franklin County voters in November 1960 allowed Metro Parks to grow, and Blacklick Woods to expand. From its base of 120 acres, Blacklick Woods grew to 392 acres by the end of 1961, and by June 1966 it had reached a size of 506 acres. The additional land allowed Metro Parks to create a new picnic area and fashion several reservable areas for group use, significantly reducing the overcrowding problems from earlier years. More importantly, it created a buffer to protect the existing swamp and beech-maple forests, while also adding more woodland to the mix. Protection of the existing natural habitat was at the forefront of Metro Parks’ thinking when the next, and final major acquisition of land was made at Blacklick Woods in August 1967 – the Stoney Creek Country Club.

THE GOLF COURSE

Blacklick Woods Golf Course, as a named entity, opened in summer 1973 and turns 50 years old in August. But golf had been a feature at the park for six years already. In financial difficulty, the Stoney Creek Country Club, sandwiched between park land to both the north and south of it, contemplated the conversion of its 18-hole golf course to a 9-hole course, and the sale of half of its land for housing development. Anxious to protect the land from housing development, the park board negotiated the purchase of the entire country club land, and took over responsibility for running the golf course in 1967. The belief was that an environmentally responsible golf course could coexist favorably with the carefully managed habitat of Blacklick Woods Metro Park. The 126 acres of the golf course was the last major purchase of land at Blacklick Woods, with just 10 acres of conservation easements added later to the park’s total of 643 acres.

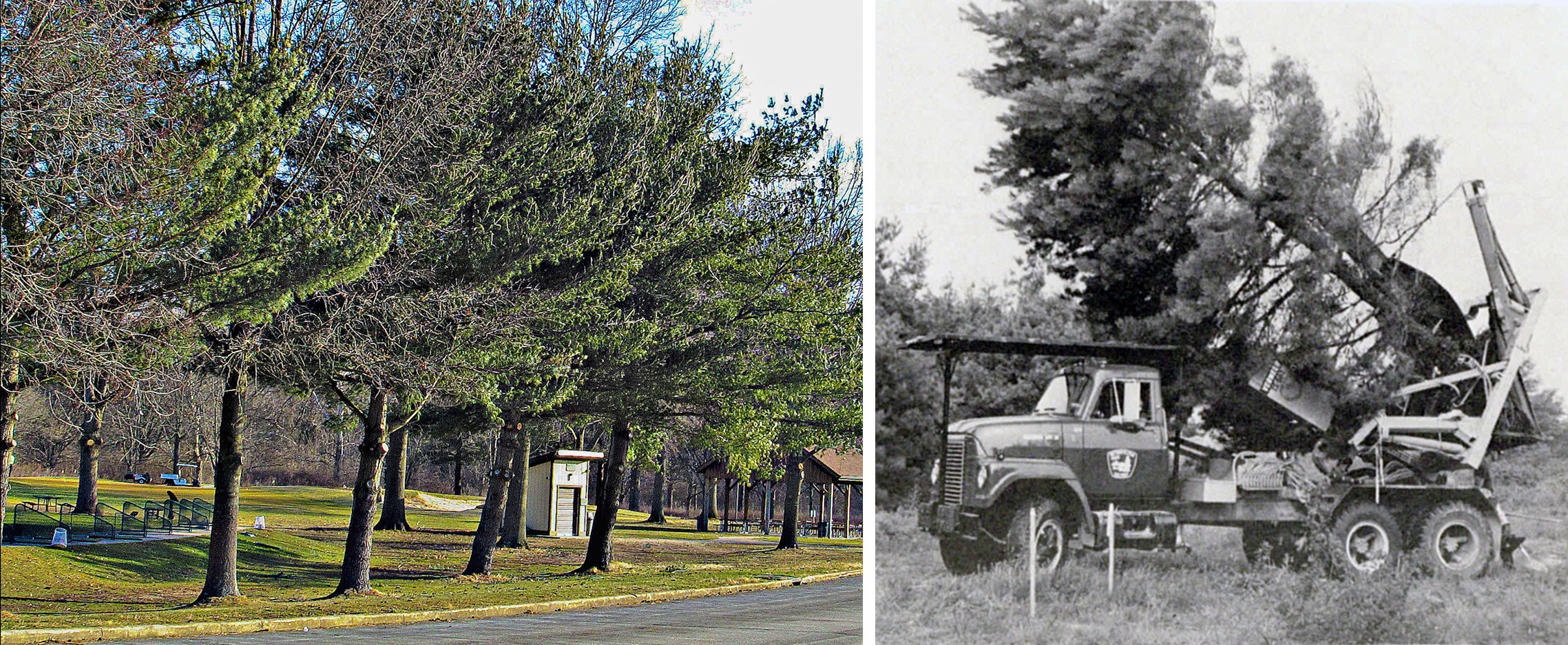

The golf course was in need of improvements. In the first year, Metro Parks tackled a long-standing problem with watering of the greens and fairways by creating a 10-inch well and pump house, rebuilt several tees, reigned back on the excessive growth of fairway rough, and replenished sand in the bunkers. As well, the parks began a turf rejuvenation program, and planted 182 evergreens and 48 deciduous trees. The course traded as The Stoney Creek Metropolitan Golf Course at Blacklick Woods and began to prosper. Not only did the course increase native habitat for the park, it also became apparent that the golf course lured a segment of the population who may not have typically visited the park. Even Governor Jim Rhodes professed that more of Ohio’s parks should provide golf courses. The continuing success as a public golf course inspired Metro Parks to plan a future extension and to rebrand the facility as the Blacklick Woods Golf Courses.

The expanded and newly-designated Blacklick Woods Golf Courses opened in 1973 and included the utilization of a 100-acre tract of land to the north of the original 18-hole course. The course itself was redesigned, utilizing the talents of Columbus golf architect Jack Kidwell, who incorporated 13 holes from the original course in a new design. This new, almost 7,000-yards Championship Course, extended northward beyond the confines of the old country club land. A second course, a shorter, par 59 Executive Course, was added in this northern area of the park. The Executive Course, at just under 4,000 yards long, proved especially popular with women and with both youth and senior golfers. The 18-hole Executive Course could be played in less than three hours, yet it required the use of every club in the golf bag and provided a true test of golf.

The Championship and Executive courses won plaudits from golfers and critics alike, but the jewel in the crown of the Blacklick Woods Golf Courses was the new Golf Course Activities Building. The building incorporated a golf pro shop, cart rental, indoor driving range, snack bar and locker and shower room for golfers. But it also contained a Banquet Room, which seated 99 people and was available for rental for parties, banquets or wedding receptions.

GOLF COURSE WINS TOP OPRA AWARD

The Ohio Parks and Recreation Association recognized the quality of Metro Parks’ achievement by granting it the association’s Outstanding Facility Award in 1974. The award, in a category for organizations in communities with populations in excess of 500,000, praised Metro Parks’ development of what OPRA described as the finest public golf complex in the Midwest.

THE PINES, THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’

The entrance to Stoney Creek Golf Course at Blacklick Woods had been located on State Route 256, east of the park. With the expansion of the golf course into the northern area of Blacklick Woods, entry was moved to Livingston Avenue. This entrance had been created a few years earlier to give access to a Day Camp, which had been set up in that northern area and now gave way to the expanded golf course. Other day camps continued in the southern area of the park.

The park also changed its main entrance in 1974, but didn’t move quite as far. The new entrance shifted about 1,500 feet, from west of to the east of the Unity Presbyterian Church. But there was a problem. Dozens of huge pine trees stood in the right-of-way of the new entry road. The prospect of losing these natural treasures was a horrendous one to contemplate. But the pines, they are a-changin’, to paraphrase Bob Dylan, and Metro Parks acquired one of the largest mechanical tree spades on the planet to safely uproot and transplant these wonderful trees. It was a case of “Don’t Pine for Me, (Argentina)” as the huge pines were safely moved and planted near the new Golf Course Activities building, where they still stand proud today, all of 50 years later. The hydraulically powered digging unit, mounted on the chassis of a large truck, allowed Metro Parks to uproot and transplant trees up to 8 inches in diameter, ideal for pines and other evergreens. The tree spade has been used to move trees in picnic areas and along roadways at many parks.

The new entry road helped to improve the distribution of traffic within the park and moved the entry closer to the new golf course entrance, both of them now on Livingston Avenue.

AUDUBON SANCTUARY CERTIFICATION

In 1995, Kinney Golf Course Design made several improvements on the Championship Course, which benefited from new greens, tees and bunkers. At the same time, Metro Parks became involved with a fledgling environmental organization called Audubon International, which coordinated an interactive program, called the Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Program (ACSP), that serves as a platform for golf courses to exhibit their initiatives to protect natural resources. Facilities which consistently demonstrate excellence are ultimately awarded Audubon certifications.

Participation in the Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Program was a natural fit for Metro Parks. In 2000 we were credited by Audubon International for our high standards with environmental planning. The following year we were recognized for our wildlife and habitat management, and for our effort to use irrigation water prudently. And soon after that, we received the society’s approbation for our environmentally-conscious use of chemicals and our practices to improve water quality. Finally, in 2005, Blacklick Woods Golf Course was designated as a Certified Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary. At the time, we were just the fourth ACSP fully certified golf course in the state of Ohio.

21st CENTURY UPGRADES FOR THE GOLF COURSE

In 2011, Metro Parks converted the 18-hole Executive Course into a 9-hole Learning Course, with two par 4s and seven par 3s, ideal for beginners, families and golfers seeking to improve their short game and iron play, and created a high-quality practice facility in the remaining area. The facilities include a full-service driving range, a very large practice green with three bunkers for sand play, and a 3-hole practice course. An innovation in 2019 saw Metro Parks offer free golf on the 9-hole Learning Course for any Franklin County resident

Eagleview, a new rental facility, opened at Blacklick Woods Golf Course in October 2018. It is the largest reservable facility in the entire park district, seating 175 people, and features a large meeting room, entrance foyer and kitchenette with a fridge, microwave and ice maker. Eagleview can be rented separately, or in combination with the Banquet Room for very large weddings. It sits prominently on the Championship Course, in close proximity to the 10th tee and 18th green.

THE PARK’S STATE NATURE PRESERVE

The 54-acre swamp forest at Blacklick Woods, part of the original 113-acre park that opened in 1948, was dedicated as a State Nature Preserve by Metro Parks in 1975. Named the Walter A. Tucker State Nature Preserve, it honors one of Metro Parks’ founding fathers, and its first Director-Secretary, who served Metro Parks with distinction for more than 25 years before retiring. The beech-maple forest in the northern area of the preserve is one of the least disturbed such forests in Ohio. The wetter southern area, a true swamp forest, features spicebush and buttonbush, along with mature white and pin oaks, white ash and various other species that thrive in wet environments, such as red maple, red elm, shagbark and bitternut hickory, hop hornbeam, American hornbeam and dogwood.

THE NATURE INTERPRETATION CENTER

Two years later, Metro Parks began construction of the new Blacklick Woods Nature Interpretation Center, which was ready to open for visitors in late spring of 1978. The center proved to be a tremendous hit with visitors. It opened every day and always had naturalists or volunteers on hand to assist visitors. As mentioned earlier, one of the main boons of the center was the special one-way picture windows, which allowed close-up views of wildlife in the adjacent pond and swamp complex. The center also hosted a changing roster of natural history exhibits and became the base or start point for many of the park’s nature education programs.

THE MULTIPURPOSE TRAIL

Construction of the nature center required Metro Parks to close a service road that had often been used by bikers as a safe means of enjoying recreational biking away from busy main roads and thoroughfares. Metro Parks had opened a very successful multipurpose trail for bikers at Sharon Woods a few years before, and the creation of a similar trail at Blacklick Woods fitted well with a conviction that adding a passive recreational trail through a natural environment was a good addition to the existing nature trails at the park. Work began in 1977 and by the following summer, the 10-foot-wide, paved 2.6-mile Multipurpose Trail opened for bikers, joggers and inline-skaters to enjoy.

THE SWAMP FOREST BOARDWALK

A new nature trail, the half-mile Buttonbush Trail, was built to connect the new Nature Interpretation Center with the park’s other nature trails. The new trail looped around the most southerly (and wettest) part of the swamp forest. Thanks to passage of the 1979 park Levy, Metro Parks was able to proceed with a capital improvements project to add ten different sections of boardwalk and three observation decks to the trail. The five-foot wide stretches of boardwalk, each of different lengths, allowed passage of the trail even during the wettest periods of the year. The observation decks were ideal locations for educational programming and scientific research by naturalists and environmentalists. Each section of boardwalk was built with a 2-inch-high curb, to allow for safe wheelchair access.

The labor was performed by members of the Young Adult Conservation Corps, who worked under Metro Parks supervision as part of a national program, which provided young people with year-round conservation-related employment and education opportunities.

BIRDING AT BLACKLICK WOODS

Way back in 1950, the nest of a pileated woodpecker was discovered at Blacklick Woods, in a tall dead beech tree. This was a rare find in those days. Metro Parks’ founding board member, Ed Thomas, said that no pileated woodpeckers had been reported anywhere near Columbus for many years.

This was the start of a love affair between birders and Blacklick Woods, which became known as a birding haven thanks to its varied habitats and wide range of species. The nesting pileated woodpeckers were an attraction for years. Today, Ashton Pond and the nature center pond and swamp are great for waterfowl, whilst the woods are terrific for seeing or hearing numerous species of woodpeckers as well as warblers and other songbirds. Red-tailed and red-shouldered hawks are common finds, and the sight of barred owls swooping across Ashton Pond has excited many a birdwatcher and photographer.

Wildlife watching is also a thrill for park visitors, and in the early 2000s led to photographers seeking to capture images of Big Red and later, the Son of Big Red, both amongst the largest white-tailed deer bucks seen anywhere in any of the Metro Parks. (See BIG RED, Search for a Legend). Other common sights of wildlife at Blacklick Woods include red and gray foxes, coyotes, mink, muskrats and weasels.

LENS AND LEAVES

The increasing prevalence of photographers at Blacklick Woods and at other Metro Parks, prompted Metro Parks to sponsor a camera club devoted to nature photography. The first meeting of the club was held at the Beech-Maple Lodge in June 1977. The idea for the club came from a local architect and photographer, Bob Fridenstine, who wrote to Metro Parks’ Director-Secretary Ed Hutchins. In return for Metro Parks’ support of the club, photographers promised to provide images to the parks for use in its publications and exhibits. In due course, the club adopted the name of the Lens & Leaves Camera Club, and it helped to organize a long-standing series of annual photo exhibits at various parks. Beech-Maple Lodge became the home for the club’s monthly meetings for almost 40 years, until Lens & Leaves met its own winter and ceased operation as a camera club due to dwindling membership.

AN INDIAN VILLAGE AT BLACKLICK WOODS

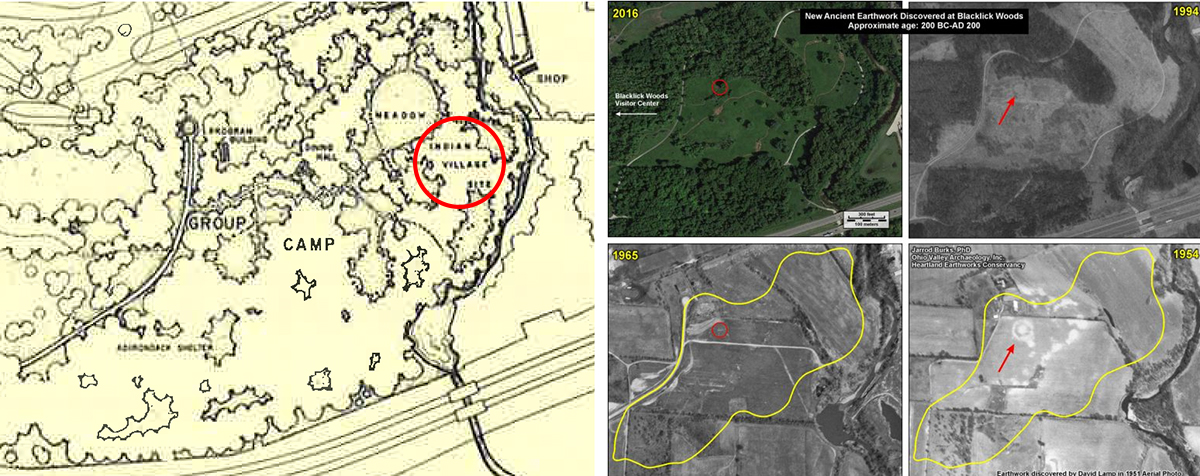

Evidence of an Indian village was found at Blacklick Woods on a 100-acre parcel of land acquired in 1961 as part of the park expansion. The former owner of the land had removed topsoil and gravel from a 5-acre area and discovered 16 firerings about 30 inches beneath the topsoil. Metro Parks asked Dr Raymond S. Baby, Curator of Archeology at the Ohio State Museum, to review the firerings. Dr Baby confirmed the authenticity of the find. After more investigations, he expressed his belief that the culture of the firerings was consistent with that of the Late Woodland Indians, who lived in Ohio between AD600 and AD1200. This fact was reported in the November-December 1961 issue of Metropolitan Park News, and maps of the park in the mid 1960s marked the area with the words “Indian Village Site.”

In 2017, archeologists from the Heartland Earthworks Conservancy discovered another find on the same 100-acre tract of land. Dr Jared Burks and colleagues had studied aerial maps of the site and identified a prehistoric circular earthwork, a little farther west of Blacklick Creek from the firerings discovered in 1961. Dr Burks conducted magnetic resonance imaging on site and concluded that the circular earthwork may have been built by an earlier culture, either the Adena or Hopewell people. (More about the 2017 discovery of a prehistoric circular earthwork)

BLACKLICK WOODS NOW AND YET TO COME

Today, Blacklick Woods features 6 miles of trails within the park, and the Blacklick Creek Greenway Trail now extends for 16 miles and connects Blacklick Woods with two other Metro Parks, Pickerington Ponds and Three Creeks. Additional sections of the Blacklick Creek Greenway Trail were built in both the southern and northern sectors of the park, connected by the existing Multipurpose Trail. The park features two large picnic areas, which together host 11 different shelters that can be used on a first-come first-served basis by picnickers. The park also boasts four reservable picnic shelters, plus Beech-Maple Lodge. The Golf Course has its own reservable facilities, the Banquet Room and Eagleview, and also features a sledding hill for winter adventurers to enjoy.

With visitor numbers steady at around 900,000 per year, the future looks bright for Blacklick Woods, the first of the current 20 Metro Parks. A new and exciting development for the near future includes the building of a tree canopy walk near the existing nature center. Visitors will rise up to the canopy, 30 feet off the ground, via an elevator tower, and then take a 500-foot looped canopy walk through the trees. The tower will include an even higher observation deck for great views across the park.

Very informative. Will you cover all parks?

Thank you, Debbie. Almost all of the parks have been written about now. There is a separate blog page with links to all the park history articles: https://www.metroparks.net/blog/category/park-histories/

Why is there no mention of the 2,000-year-old Native American earthwork that my colleague Jarrod Burks and I, from Heartland Earthworks Conservancy, found in the park a few years ago?

Thank you for your comment. I have added a couple of paragraphs to the article about the earthwork you discovered in 2017, and about the firerings discovered on the same tract of land in 1961, a little nearer to Blacklick Creek.