With each passing month from spring to fall, the farm’s Percheron draft horses are kept busy as the driving forces behind the farm’s vast array of machinery and tools for field preparation. Whether it be plowing or harrowing fields, mowing to loading hay, I find it fascinating to watch these amazing animals in action. However, revealing itself in the month of July, there is one piece of essential horse-powered machinery that I’m particularly fond of—the threshing machine.

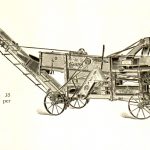

In the 1880s, the horse-powered threshing machine was used in the final stage of harvesting grain such as wheat, oats, barley, buckwheat and rye. Hand-fed into the machine, a heavy cylinder “threshes” the grain, separating the seed-heads from the seed covering and stalks. Modern-day farmers complete this process with a combine that cuts and threshes all at once as they drive through their fields.

At Slate Run Living Historical Farm we grow wheat and oats, two essential grains that Samuel Oman harvested when he occupied the land in the late 19th century. We only harvest three acres, while Mr. Oman harvested 65. It was common for farms in neighboring areas to gather a crew, or threshing ring, and take turns threshing one another’s fields.

I’ll never forget when I first saw the threshing machine during my first year as the intern at Slate Run Farm. Seeing it when it was not in operation was astounding enough, with its intricate set of gears and rods, the tall conveyor extending toward the wooden pole around which the straw would be stacked, and the very conspicuous mound of wheat that sat atop the wagon parked next to the machine. The wheat had been cut and bound by twine into individual small bundles called sheaves, this being achieved by another fascinating horse-powered machine, the

reaper-binder.

In the 1880s, women would not usually participate in field work in Ohio. One of the many reasons why I love interning at the farm is that, though we acknowledge and for the most part adhere to the gender roles that were present during the time-period, everyone that is willing to experience a component of history is encouraged and welcomed, regardless of their gender. I remember that my coworker Donna and I got to help the guys arrange the sheaves in shocks in order for the wheat to dry before being brought in on the wagon. Shocking wheat, as it was called, was not likely to be a task a farm wife would do during the grain harvest. Even more unlikely was a farm wife pitching sheaves, but at Slate Run Farm, when we are short on men, the women pitch in as well.

As I watched in fascination the horses walk in a rhythmic circle, transmitting energy to the threshing machine through a long rod and belt, I would not have guessed at first that I was soon to be a part of the threshing crew. Soon enough though, after a practice-run, there I was, standing atop the mound of wheat sheaves. I was wearing the shortest yet still socially acceptable dress I could find so as not to fret about stepping on my hem while moving about the wagon.

With a sun-hat on my head, a protective scarf around my neck, and pitchfork in hand, I felt that Rachel the sheave-pitcher was an unusual spectacle to some of the visitors. I had never felt such a great feeling than that which I experienced while standing on what seemed like a mountain of grain, knowing that I was playing a part in showing people of all walks of life how the fascinating process of horse-powered threshing was done over 130 years ago.

With everyone in position, the guys yelled “Ready” and the horses began to walk. My coworker Natelle fed the sheaves into the machine as I pitched to her from the top of the wagon. I had to be careful not to wield my pitchfork too close to her as I pitched, as she was only a few feet from me. Some of the sheaves were thicker than others and were difficult to pitch. I dropped quite a few, but after a while, I managed to get the hang of it. Natelle proved to be excellent at catching the sheaves and feeding them into the machine. She was as fast as lightning. We got into a nice rhythm, and one by one, each sheaf made its way into the threshing machine.

The seed-head covering, or the chaff, was blown away by a fan, and out of a side chute the clean seeds dropped into bushel bags. The stalks, or straw, made its way up the long conveyor, falling in a heap at the base of the tall wooden pole around which a team of two to three people were stacking the straw with pitchforks. After about two hours, we had half of one wagon-load done out of what would be around eight in total. Noon came quickly, and that meant time for what is historically regarded by many who experienced threshing growing up as the best part of the whole event; the threshing meal.

The threshing meal was the social and culinary staple of the grain harvest. It provided family members and neighbors a chance to come together to reaffirm friendships and bonds, and even promote courting and marriages among men and women. There was a strong sense of comradery among the threshing ring and their families, all sharing in the responsibility of the grain harvest.

Today, the threshing meals are best remembered for their culinary aspects. They gave women a chance to show off their skills in the kitchen and promote friendly competition among the other hostesses.The importance of the table setting and atmosphere of the eating area was also heightened. A good hostess pulled out her “guest” cloths, special table cloths and tableware. Women and girls were assigned to serve the threshing crew and often had special aprons set aside to change into to look presentable when serving. Women and children ate only after the men were finished at the table. It was a meal associated with high status, and understandably put quite a bit of pressure on a farm wife. However, some of this stress was alleviated by having help from other women in the neighborhood.

The grain harvest at Slate Run Farm is definitely not as stressful or as rigid for us women as it was back in the 1880s, but we still prepare a large and wonderful feast and serve the men at the table. As was common in the 1880s, we ladies start preparing for the two threshing meals we host days in advance. Besides the meal itself, I love how we reflect even the social importance of threshing; the togetherness, if you will.

Numerous farm volunteers, both new and old, come out to be a part of the threshing ring, all working to restore and re-live a captivating piece of agricultural history. I feel very privileged to have been a part of it, and am excited to take part in it once again this July.

RACHEL BROOKS

Intern at Slate Run Living Historical Farm (studying Wildlife Management at Hocking College)

(THRESHING PROGRAMS IN JULY 2017 — see the horses, staff and volunteers at work)

Sat July 15, 1–3pm Sun July 16, 1–3pm

- Sheaves of wheat in the fields at Slate Run Farm.

- The separated wheat grain after threshing.

- Staff take a break after a threshing session.

- Sheaves of wheat are pitched down to go into the threshing machine.

- Wheat is guided into the threshing machine.

- Slate Run Farm uses the Champion No 1 threshing machine, a model which was sold from the late 1880s through the 1910s.

- A mountain of stalks and seed covering is left after the seeds are threshed from the wheat or oats.

- Wheat is transferred from the fields to a wagon for transport to the threshing machine.

- Sheaves of wheat are transported from the fields on horse-drawn wagon for threshing. (Frank Kozarich)