Launching into wild edible plants may seem complicated, but with a little knowledge and an adventurous mindset, you could be foraging for your own food in no time. Before you get started, enter with a mindset of SAFETY FIRST! Certain plants can have either acute or underlying toxins and some may even have both.

Launching into wild edible plants may seem complicated, but with a little knowledge and an adventurous mindset, you could be foraging for your own food in no time. Before you get started, enter with a mindset of SAFETY FIRST! Certain plants can have either acute or underlying toxins and some may even have both.

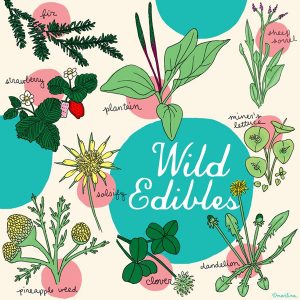

The first thing to do is to learn to identify plants. I recommend A Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants: Eastern and central North America by Lee Allen Peterson. Although you cannot collect plants from any of the Metro Parks or State Parks, there are plenty of opportunities for you to forage for wild edibles nearby. You can also forage for plants in State and National Forests.

Wild edible plants: black walnut

If you have a walnut tree nearby or if you frequent many of our Columbus and Franklin County Metro Parks, you may be familiar with the resounding thump of black walnuts falling to the ground every September and October. These fruits resemble tennis balls in both size and color as they drop from the trees above. Even though you might feel the need for a hard hat, the tree is dropping a delicious and plentiful gift for the squirrels and foragers alike.

Black walnut, Juglan nigra, is a native deciduous tree that can be found growing in rich, moist soils. It is also commonly cultivated and can be found growing in residential and urban areas. If you have one growing in your yard, you might know that growing other plants under and around black walnut trees can be challenging. That is because this tree produces a chemical known as juglone in its roots, leaves and fruit husks. This chemical prohibits the growth of many other plants and therefore limits the competition, leaving more water and nutrients for the walnut tree. Juglone can also be used as a natural dye for clothes and fabric. Proof of this powerful dye can be discovered just by handling the fruits.

A tall tree, black walnut can grow 50 to 75-feet high with large, fragrant, compound leaves. The beautiful wood is highly sought after for veneer and other woodworking projects, but we are here to talk about the fruit. Black walnuts are nearly round and are 2” in size. They are protected by a green, fleshy husk that turns dark brown as it ages and it too has a unique fragrance. Inside this husk is an extremely hard, rounded nut with rough and irregular grooves and ridges. While difficult to extract, the sweet and tasty nutmeat inside is well worth the effort.

If you are hoping to harvest and process some black walnuts yourself, you will first need to locate a walnut tree. Many people with walnut trees on their property, find the fruit a nuisance and may be receptive to you offering to clean up their yard for them and remove the nuts. Then, you will need to wait for the fall for the fruits to ripen. Typically, black walnuts fall as the leaves on their trees turn yellow and begin to fall themselves in late September and October.

Begin collecting the nuts as they fall and remove the husks immediately. I find the best way to remove the husk is to wait for them to brown just slightly enough to soften up and then simply step on them, apply a little pressure, and roll the fruit until the husk comes off. It is best to do this with an old pair of shoes and thick gloves, because the juglone in the husks will stain. Everybody has a unique and creative way that they think is the best to remove the husks, but I think this is the simplest. Try to get as much of the husk off as possible, but it is okay for it to not be entirely clean.

Next, you will want to rinse the nuts to remove what is left of the outer husk to reveal the hard shell. Place the nuts in a large bucket and hose them down while shaking and stirring the nuts. The agitation of the roughly ridged nuts will help clean them. Repeat this step a few times, until the nuts are mostly devoid of any husk material. Now it is time to dry the walnuts. To do so, you can either spread the walnuts in a thin layer, preferably on a screen or drying rack, or hang them in a mesh bag in a well ventilated area that is out of direct sunlight for a couple of weeks. Once fully dried, the unshelled walnuts can be stored in a breathable container for up to a year. If you do not want to store them unshelled, it is now time to get cracking.

Black walnuts have a hard shell that will defeat most common nutcrackers. There are specialty nutcrackers that can handle black walnuts, but if you are not ready to invest in one they can be cracked with a hammer, rock, or a vice. Use what is available and what works best for you. Hold the walnut tightly and gently strike the nut with a hammer at a 90 degree angle to the seam until it cracks. Toss everything, the nutmeat and shell, into a bucket or bowl to sort later.

Once opened, you will notice that the inside of a black walnut is complex and multi-chambered, which can make getting the nutmeat out a challenge. I find that using a pair of cutting pliers to strategically clip away pieces of hard shell helps to release the nutmeat. As you sort through, removing the nutmeat, be careful to remove all pieces of the shells. Double check to ensure that all hard pieces of shell are removed, as you would not want to accidentally chomp down on one. Allow the freshly removed nutmeat to dry for a day before storing.

Black walnuts can be enjoyed raw and have an interestingly sweet and earthy taste to them that goes great on top of desserts, such as ice cream or cupcakes. They can also be dipped in a sugar syrup and enjoyed as a candy or ground to a meal and made into a flour.

(Cody Berkebile, naturalist at Blacklick Woods)